Japanese tattooing

Japanese tattooing occupies its own revered place in ink legend. And from the stunning full-body suits to the minimalistic studios and the elegant hand-poking Tebori tools, what’s not to be in awe of. One of the true classics of the global tattoo trade, let’s take a closer look at the legacy of ink from Japan.

Poetry in a name

The distinctive style of Japanese tattooing is called Irezumi, which can be translated as “inserting ink.” It is also known as bunching – “patterning the body”, shishei – “piercing with blue” or get, which literally means, well, tattooing.

The tradition of tattooing in Japan is thought to reach very far back. Some even claim there is evidence of it beginning around 10,000 BC. However, the generally agreed-upon date is about 5,000 years later, the period from which primitive clay figurines have been discovered in tombs, adorned with tribal style tattoos.

Meanwhile, there is no known record of tattooing being a widely spread practice on the Japanese mainland. During the Kofun period, 300 to 600 AD, they began to take on negative connotations. Criminals were branded with things like bands, symbols, Japanese characters, or dots in visible places, like the hands or forehead, in place of serving long sentences in prison.

Mostly reserved for women

Early tattoos were mostly reserved for the women of the Ainu, also known as the Ezo, and ancient Okinawan tribes known as Uchinanchu. The former had mouth tattoos, made from rubbing ash into small incisions. Performed by a priestess, they symbolised social status or coming of age. The latter wore blue markings on their hands, to proclaim social standing, while also serving spiritual and religious purposes.

Early tattoos were mostly reserved for the women of the Ainu, also known as the Ezo, and ancient Okinawan tribes known as Uchinanchu. The former had mouth tattoos, made from rubbing ash into small incisions. Performed by a priestess, they symbolised social status or coming of age. The latter wore blue markings on their hands, to proclaim social standing, while also serving spiritual and religious purposes.

The markings were thought to ward off evil spirits and demons. However, as a result of the negative association from the branding of criminals, these tattooing practices were outlawed in Japan sometime in the 18th century.

While wishing to portray itself as a sophisticated nation in its relationship to European states, the ban also meant that the government could destroy the spiritual traditions that went along with the female tattooing custom. This saw women as emissaries of the spirit realms, and as such in possession of special powers. And the centralised patriarchal government was, of course, having none of it.

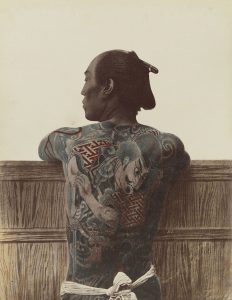

Meanwhile, there was still tattooing going on. Those opposed to the government’s rule, be that due to gang affiliation or simply a union-esque attitude, continued to get inked clandestinely.

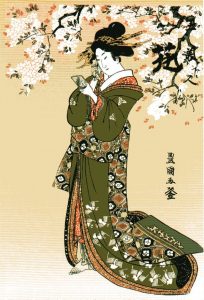

Ukiyo-e

What shaped the style of Japanese tattooing more than anything was the art movement known as Ukiyo-e. Widely popular between the 17th and 19th centuries, its artists produced woodblock prints and paintings with motives ranging from female beauties, kabuki actors and sumo wrestlers to folk tales, landscapes and even erotic scenes. The style was characterized by flattened perspectives, delicate linework and the use of negative space.

In the next post, we will take a closer look at the imagery in modern-day Japanese tattooing, its legal status, and how it is viewed in Japanese society today.