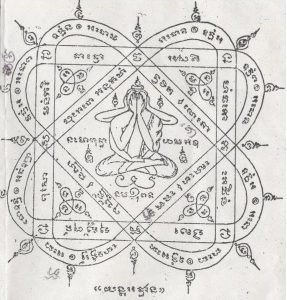

While the state laws on tattooing are not so harsh, should you get a traditional (and considered magic) Sak Yant tattoo by a Thai Buddhist monk, there are a number of rules of conduct to follow post-needle. The Sak Yant tattoos were originally done on warriors seeking strength and protection in battle and are still considered a manifestation of desire or intention. South East Asian communities consider these marking to be very powerful and that they bestow blessings on the bearer. In order for the tattoos to retain the special powers imbued in them by the monk masters (women are not allowed to get a tattoo in a temple, but must go to a blessed area outside where monks can visit to perform them) the recipient needs to adhere to a strict code of conduct both during, and in the time after, having it done. These follow the Buddhist moral code and are:

1. Do not kill

2. Do not steal

3. Do not be unfaithful to your spouse

4. Do not lie

5. Do not get intoxicated

6. Do not speak ill of anyone’s mother

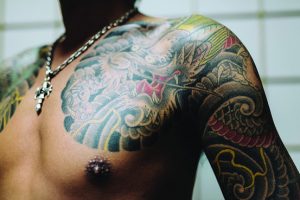

Japan has a particularly complicated historical relationship to tattoos. Body art dates back over 2000 years in Japan, but has been heavily stigmatised as it is associated with the Yakuza, the infamous organised crime syndicate famous for their elaborate tattoos, which still has a strong hold on much of Japanese society. Officially it is, just as in South Korea, illegal to perform a tattoo unless you are a licensed doctor. Tattoos were entirely banned in Japan from the 1800s to the 1940s and then soon after the end of WWII the medical license law was introduced as a way of loosening the harsh restrictions.

This law is rarely enforced however, and tattoo parlours and artists operate int the open without any repercussions. That is, until a couple of years ago, when a court in Osaka suddenly fined a tattoo artist heavily for operating his business without having a medical license. Thankfully, this ruling was overruled on appeal only a year later, uprooting what could have been the start of a dangerous precedence and practice by the courts. In spite of the fact that most newly minted Yakuza members opt out of distinguishing body art in order to fly under the radar after government crackdowns, attitudes towards openly displayed tattoos are slow to shift. Many public spaces in Japan, such as gyms and pools and the traditional bath houses known as onsens ban people from openly displaying their tattoos, so as not to frighten other guests. Apart from the criminal connotations, there is also a Konfucian cultural heritage at play that insists that one should not alter the body one has been given by one’s parents.

In China, the government has forbidden all of their football players to have any tattoos on display during games, and banned any visible ink from TV. In addition, it is barring any performer representing ‘hip-hop culture’, ‘subculture’ or ‘dispirited culture’ (what they dub non-dogmatic decadence existing outside party preference). Just as in Japan, tattoos were for a long time associated specifically with organised crime. The Triads, just as the Yakuza, adorned their bodies with large scale designs. They begun gaining in popularity in earnest with the 2008 Olympics in Beijing when visiting foreigners openly displayed their body art on the streets and arenas of the Chinese capital. When the Communist Party came to power following WWII, Mao completely outlawed tattoos. Today, the industry falls somewhere in a grey area — not illegal, but not entirely officially recognised either, and the government could technically close down any tattoo studio it wishes to, as there is no licence to be filed for. With the other trends towards a technically superior surveillance state in China, with people earning or losing points in a rating system depending on how ‘good a citizen’ they are, it remains to be seen what this will mean for those creating art on other people’s skin as their profession.